Scoliosis

Highlights

Overview

- The spine is a column of small bones, or vertebrae, that supports the entire upper body. Scoliosis is an abnormal curving of the spine.

- About 10% of adolescents have some degree of scoliosis, but fewer than 1% of them develop scoliosis that requires treatment.

- Among persons with relatives who have scoliosis, about 20% develop the condition.

- In 80% of patients, the cause of scoliosis is unknown. Such cases are called idiopathic scoliosis.

Screening

- Screening programs for scoliosis, which began in the 1940s, are now required in middle or high schools in many states, but there is considerable debate over whether screening programs are effective.

- A recent review of previous studies found that using the forward bend test alone in school screenings is not sufficient, but not enough data exists on the usefulness of other tests in screening programs.

Treatment Approaches

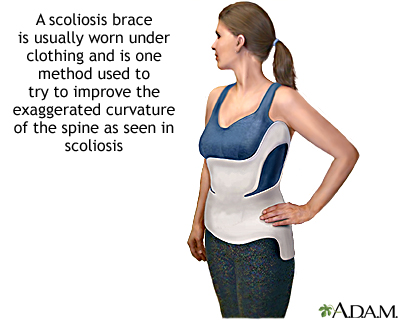

- Braces tend to be used in children with curvatures between 25 - 40 degrees who still will be growing significantly.

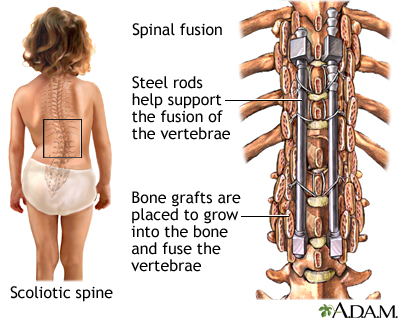

- Most scoliosis operations involve fusing the vertebrae. The instruments and devices used to support the fusion vary, however.

- Increasingly, surgeons are using the anterior approach, in which the surgeon performs the operation through the chest wall to correct the spinal curve. Because the frontal approach allows the procedure to be performed higher up in the spine than standard procedures, the patient may have a lower risk for lower-back injury later on. In addition, transfusion rates are much lower with the anterior approach.

Introduction

Scoliosis affects about 2 - 3% of the United States population (about 6 million people). It can occur in adults, but it is more commonly diagnosed for the first time in children aged 10 - 15 years. About 10% of adolescents have some degree of scoliosis, but fewer than 1% of them develop scoliosis that requires treatment. The condition also tends to run in families. Among people with relatives who have scoliosis, about 20% develop the condition.

Scoliosis that is not linked to any physical impairment, as well as scoliosis linked to a number of spine problems, may be seen in the adult population as well.

The Spine

Vertebrae. The spine is a column of small bones, or vertebrae, that support the entire upper body. The column is grouped into three sections of vertebrae:

- Cervical (C) vertebrae are the 7 spinal bones that support the neck.

- Thoracic (T) vertebrae are the 12 spinal bones that connect to the rib cage.

- Lumbar (L) vertebrae are the 5 lowest and largest bones of the spinal column. Most of the body's weight and stress falls on the lumbar vertebrae.

Each vertebra can be designated by using a letter and number; the letter reflects the region (C=cervical, T=thoracic, and L=lumbar), and the number signifies its location within that region. For example, C4 is the fourth vertebra down in the cervical region, and T8 is the eighth thoracic vertebra.

Below the lumbar region is the sacrum, a shield-shaped bony structure that connects with the pelvis at the sacroiliac joints. At the end of the sacrum are 2 - 4 tiny, partially fused vertebrae known as the coccyx or "tail bone."

The Spinal Column and its Curves. Altogether, the vertebrae form the spinal column. In the upper trunk, the column normally has a gentle outward curve (kyphosis) while the lower back has a reverse inward curve (lordosis).

The Disks. Vertebrae in the spinal column are separated from each other by small cushions of cartilage known as intervertebral disks. Inside each disk is a jelly-like substance called the nucleus pulposus, which is surrounded by a tough, fibrous ring called the annulus fibrosis. The disk is 80% water. This structure makes the disk both elastic and strong. The disks have no blood supply of their own, relying instead on nearby blood vessels to keep them nourished.

Processes. Each vertebra in the spine has a number of bony projections, known as processes. The spinous and transverse processes attach to the muscles in the back and act like little levers, allowing the spine to twist or bend. The particular processes form the joints between the vertebrae themselves, meeting together and interlocking at the zygapophysial joints (more commonly known as facet or z joints).

Spinal Canal. Each vertebra and its processes surround and protect an arch-shaped central opening. These arches, aligned to run down the spine, form the spinal canal, which encloses the spinal cord, the central trunk of nerves that connects the brain with the rest of the body.

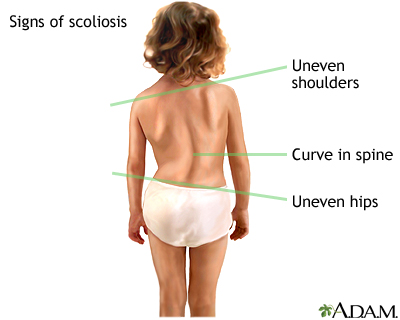

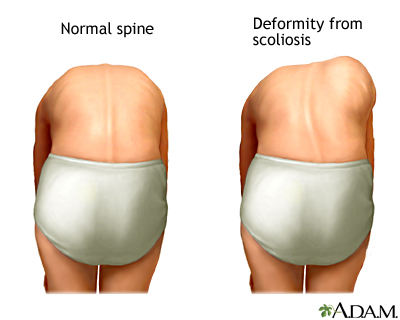

Scoliosis is an abnormal curving of the spine. The normal spine has gentle natural curves that round the shoulders and make the lower back curve inward. Scoliosis typically causes deformities of the spinal column and rib cage. In scoliosis, the spine curves from side-to-side to varying degrees, and some of the spinal bones may rotate slightly, making the hips or shoulders appear uneven. It may develop in the following way:

- As a single primary side-to-side curve (resembling the letter C)

- As two curves (a primary curve along with a compensating secondary curve that forms an S shape)

Scoliosis usually develops in the area between the upper back (the thoracic area) and lower back (lumbar area). It may also occur only in the upper or lower back. The doctor attempts to define scoliosis by the following characteristics:

- The shape of the curve

- Its location

- Its direction

- Its magnitude

- Its causes, if possible

The severity of scoliosis is determined by the extent of the spinal curve and the angle of the trunk rotation (ATR). It is usually measured in degrees. Curves of less than 20 degrees are considered mild and account for 80% of scoliosis cases. Curves that progress beyond 20 degrees need medical attention. Such attention, however, usually involves periodic monitoring to make sure the condition is not becoming worse.

Defining Scoliosis by the Shape of the Curve

Scoliosis is often categorized by the shape of the curve, usually as either structural or nonstructural.

- Structural scoliosis: In addition to the spine curving from side to side, the vertebrae rotate, twisting the spine. As it twists, one side of the rib cage is pushed outward so that the spaces between the ribs widen and the shoulder blade protrudes (producing a rib-cage deformity, or hump). The other half of the rib cage is twisted inward, compressing the ribs.

- Nonstructural scoliosis: The curve does not twist but is a simple side-to-side curve.

Other abnormalities of the spine that may occur alone or in combination with scoliosis include hyperkyphosis (an abnormal exaggeration in the backward rounding of the upper spine) and hyperlordosis (an exaggerated forward curving of the lower spine, also called swayback).

Defining Scoliosis by Its Location

The location of a structural curve is defined by the location of the apical vertebra. This is the bone at the highest point (the apex) in the spinal hump. This particular vertebra also undergoes the most severe rotation during the disease process.

Defining Scoliosis by Its Direction

The direction of the curve in structural scoliosis is determined by whether the convex (rounded) side of the curve bends to the right or left. For example, a doctor will diagnose a patient as having right thoracic scoliosis if the apical vertebra is in the thoracic (upper back) region of the spine, and the curve bends to the right.

Defining Scoliosis by Its Magnitude

The magnitude of the curve is determined by taking measurements of the length and angle of the curve on an x-ray view.

Causes

Physical Abnormalities. Researchers are investigating possible physical abnormalities that may cause imbalances in bones or muscles that would lead to scoliosis. Some research suggests that imbalances in the muscles around the vertebrae may make children susceptible to spinal distortions as they grow.

Problems in Coordination. Some experts are looking at inherited defects in perception or coordination that may cause unusual growth in the spine of some children with scoliosis.

Other Biological Factors. Several other biological factors are being investigated for some contribution to scoliosis:

- Elevated levels of the enzyme matrix metalloproteinases may cause abnormalities in components in the spinal disks, contributing to disk degeneration.

- Abnormalities in a protein called platelet calmodulin that binds to calcium. This protein acts like a tiny muscle and pulls clots together.

Idiopathic Scoliosis

In 80% of patients, the cause of scoliosis is unknown. Such cases are called idiopathic scoliosis. (Idiopathic means without a known cause.) Idiopathic scoliosis may be due to multiple, poorly understood inherited factors, most likely from the mother's side. However, the severity often varies widely among family members who have the condition, suggesting that other factors must be present.

Idiopathic scoliosis may be classified based on age of presentation. Age of onset may also determine the treatment approach. The classification is as follows:

- Infantile: Up to 3 years old

- Juvenile: Four to 9 years old

- Adolescent: Ten years old through the teen years

Idiopathic scoliosis may be initially diagnosed in adults during evaluation for other back complaints or disorders, although the curve is unlikely to be significant.

Congenital Scoliosis

Congenital scoliosis is caused by inborn spinal deformities that may result in absent or fused vertebrae. Kidney problems, particularly having only one kidney, often coincide with congenital scoliosis. The condition usually becomes evident at either age 2 or in children ages 8 - 13 as the spine begins to grow more quickly, putting additional stress on the abnormal vertebrae. It is essential to diagnose and monitor such curvatures as early as possible, since they can progress quickly. Early surgical treatment -- before age 5 -- may be important in many of these patients to prevent serious complications.

Neuromuscular Scoliosis

Neuromuscular scoliosis may result from a variety of causes, including:

- A traumatic spine injury

- Neurological or muscle disorders

- Cerebral palsy

- A traumatic brain injury

- Poliomyelitis (Polio)

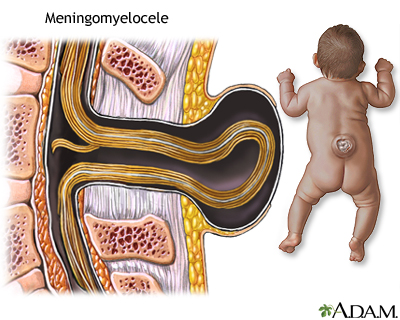

- Myelomeningocoele (a defect of the central nervous system)

- Spinal muscle dystrophy

- Spinal cord injuries

- Myopathies (muscle damage)

These patients frequently have significant complications, including an increased risk for skin ulcers, lung problems, and significant pain.

Causes of Scoliosis in Adults

Adult scoliosis has two primary causes:

- Progression of childhood scoliosis.

- Degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Degenerative lumbar scoliosis is a condition that typically develops after age 50. With this condition, the lower spine is affected, usually due to disk degeneration. Osteoporosis, a serious problem in many older adults, is not a risk factor for new-onset scoliosis, but it can be a contributing factor. In most cases, however, it is not known why scoliosis occurs in adults.

Conditions that Affect the Spinal Column and Surrounding Muscles

Scoliosis may be a result of various conditions that affect bones and muscles associated with the spinal column. They include the following:

- Tumors, growths, or other small abnormalities on the spinal column. These spinal abnormalities may play a larger role in causing some cases of scoliosis than previously thought. For example, syringomyelia, a disorder in which cysts form along the spine, can cause scoliosis.

- Stress fractures and hormonal abnormalities that affect bone growth in young, competitive athletes.

- Turner syndrome, a genetic disease in females that affects physical and reproductive development.

- Other diseases that can cause scoliosis are Marfan syndrome, Aicardi syndrome, Friedreich ataxia, Albers-Schonberg disease, rheumatoid arthritis, Cushing syndrome, and osteogenesis imperfecta.

Risk Factors

Risk Factors for Idiopathic Scoliosis. Idiopathic scoliosis, the most common form, occurs most often during the growth spurt right before and during adolescence. (Between 12 - 21% of idiopathic cases occur in children ages 3 - 10 years, and less than 1% in infants.) Mild curvature (under 20 degrees) occurs about equally in girls and boys, but curve progression is 10 times more likely to occur in girls. Being taller than average at earlier ages may put some girls at risk, but other factors must be present to produce scoliosis. A risk factor that affects females is delayed onset of menstruation, which can prolong the growth spurt period, thus increasing the possibility for the development of scoliosis.

Risk Factors for Curvature Progression. Once scoliosis is diagnosed, it is very difficult to predict who is at highest risk for curve progression. About 2 - 4% of all adolescents develop curvature of 10 degrees or more, but only about 0.3 - 0.5% of teenagers have curves greater than 20 degrees, which requires some medical attention.

Medical Risk Factors

People with certain medical conditions that affect the joints and muscles are at higher risk for scoliosis. These conditions include rheumatoid arthritis, muscular dystrophy, polio, and cerebral palsy. Children who receive organ transplants (kidney, liver, and heart) are also at increased risk.

Young Athletes

Scoliosis may be evident in young athletes, with a prevalence of 2 - 24%. The highest rates are observed among dancers, gymnasts, and swimmers. The scoliosis may be due in part to loosening of the joints, delay in the onset of puberty (which can lead to weakened bones), and stresses on the growing spine. There have also been isolated reports of a higher risk for scoliosis in young athletes who engage vigorously in sports that put an uneven load on the spine. These include figure skating, dance, tennis, skiing, and javelin throwing, among other sports. In most cases, the scoliosis is minor, and everyday sports do not lead to scoliosis. Exercise has many benefits for people both young and old and may even help patients with scoliosis.

Prognosis

In general, the severity of the scoliosis depends on the degree of the curvature and whether it threatens vital organs, specifically the lungs and heart.

- Mild Scoliosis (less than 20 degrees). Mild scoliosis is not serious and requires no treatment other than monitoring.

- Moderate Scoliosis (25 - 70 degrees). It is still not clear whether untreated moderate scoliosis causes significant health problems later on.

- Severe Scoliosis (more than 70 degrees). If the curvature exceeds 70 degrees, the severe twisting of the spine that occurs in structural scoliosis can cause the ribs to press against the lungs, restrict breathing, and reduce oxygen levels. The distortions may also cause dangerous changes in the heart.

- Very Severe Scoliosis (more than 100 degrees). Eventually, if the curve reaches more than 100 degrees, both the lungs and heart can be injured. Patients with this degree of severity are susceptible to lung infections and pneumonia. Curves greater than 100 degrees increase mortality rates, but this problem is very uncommon in America.

Some experts argue that simply measuring the degree of the curve may not identify patients in the moderate and severe groups who are at greatest risk for lung problems. Other factors (spinal flexibility, the extent of asymmetry between the ribs and the vertebrae) may be more important in predicting severity in this group.

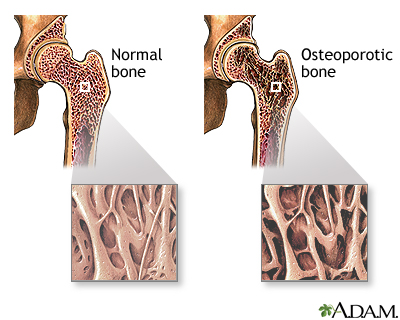

Effects on Bones

Scoliosis is associated with osteopenia, a condition characterized by loss of bone mass. Many adolescent girls who have scoliosis also have osteopenia. Some experts recommend measuring bone mineral density when a patient is diagnosed with scoliosis. The amount of bone loss may help predict how severely the spine will curve. Preventing and treating osteopenia may help limit further curve progression.

If not treated, osteopenia can later develop into osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a more serious loss of bone density that is common among postmenopausal women. Adolescents who have scoliosis are at increased risk of developing osteoporosis later in life.

Spine Problems in Previously Treated Scoliosis Patients

After 20 years or more, scoliosis patients who were previously treated with surgery experience small but significant physical impairments (mainly mild back problems), compared to their peers without scoliosis. More people with a history of scoliosis report having to take days off from work, compared to people who never had the condition. In general, however, most patients experienced a similar quality of life to peers who never had the condition.

The following are some possible causes of later back problems in people with a history of treated scoliosis:

- Spinal fusion disease. Patients who are surgically treated with fusion techniques lose flexibility and may have weakness in back muscles due to injuries during surgery.

- Disk degeneration and low back pain. With disk degeneration, the disks between the vertebrae may become weakened and rupture. In some patients, particularly those treated with the early types of Harrington rods, years after the original surgeries the weight of the instrumentation can cause disk and joint degeneration severe enough to require surgery. Treatment may involve removal of the old rods and extension of the fusion into the lower back. Still, most patients do not feel significant back pain from these problems.

- Height loss. Fusion of the spine may inhibit growth somewhat. However, much of the growth takes place in long bones, which are not affected.

- Lumbar flatback. This condition is most often the result of a scoliosis surgical procedure called the Harrington technique, which eliminated lordosis (the inward curve in the lower back). Adult patients with flatback syndrome tend to stoop forward. They may experience fatigue and back and even neck pain.

- Rotational trunk shift (uneven shoulders and hips).

Evidence suggests that previous treatment with braces may also cause mild back pain and more missed days of work, but problems appear to be less common than with surgery. In one study, dysfunction was comparable to people without a history of scoliosis.

Problems in Adult-Onset or Untreated Childhood Scoliosis

Pain in adult-onset or untreated childhood scoliosis often develops because of posture problems that cause uneven stresses on the back, hips, shoulders, necks, and legs.

Many individuals with untreated scoliosis will develop spondylosis, an arthritic condition in the spine. The joints become inflamed, the cartilage that cushions the disks may thin, and bone spurs may develop. If the disk degenerates or the curvature progresses to the point that the spinal vertebrae begin pressing on the nerves, pain can be very severe and may require surgery. Even surgically treated patients are at risk for spondylosis if inflammation occurs in vertebrae around the fusion site.

Long-Term Emotional Impact of Scoliosis and Its Treatments

Emotional Impact in Childhood. The emotional impact of scoliosis, particularly on young girls or boys during their most vulnerable years, should not be underestimated. Adults who have had scoliosis and its treatments often recall significant social isolation and physical pain. Follow-up studies of children who had faced scoliosis without having strong family and professional support often report significant behavioral problems. Fortunately, current treatments are solving many of the problems that previous generations had to deal with, including unsightly bracing and extremely painful surgeries with little pain control.

Emotional Effects in Adults. Of some concern are the growing numbers of adults with scoliosis. This group has considerable problems with general health, social functioning, emotional and mental health, and pain.

Older people with a history of treated scoliosis may carry negative emotional events into adulthood that have their roots in their early experiences with scoliosis. Patients who were treated for scoliosis may often have limited social activities, a poorer body image, and slight negative effect on their sexual life. Pain appears to be only a minor reason for such limitation.

Effects on Pregnancies and Reproduction

Women who have been successfully treated for scoliosis have only minor or no additional risks at all for complications during pregnancy and delivery. A history of scoliosis does not endanger the child. Pregnancy itself, even multiple pregnancies, does not increase the risk for curve progression. Women who have severe scoliosis that restricts the lungs, however, should be monitored closely.

Respiratory impairment

Patients with severe deformities, particularly those with underlying neuromuscular disorders, may develop what is called restrictive thoracic disease. This term refers to problems in breathing and, at times, trouble obtaining enough oxygen due to a smaller chest cavity. This smaller chest cavity results from the deformities or surgery. The restricted chest cavity is also less able to expand when breathing.

Risks of Cancer from Multiple X-Rays

Some evidence suggests a slightly higher risk for breast cancer and leukemia in patients who had multiple x-rays. Risks are highest in patients who had the largest radiation exposure, such as those who had been surgically treated.

Patients who simply received x-rays for untreated idiopathic scoliosis, or scoliosis caused by uneven length of the legs or hip abnormalities have a very low risk for future complications.

Symptoms

Scoliosis is often painless. The curvature itself may often be too subtle to be noticed, even by observant parents. Some parents may notice abnormal posture in their growing child that includes:

- A tilted head that does not line up over the hips

- A protruding shoulder blade

- One hip or shoulder that is higher than the other, causing an uneven hem or shirt line

- An uneven neckline

- Leaning more to one side than the other

- In developing girls, breasts appearing to be of unequal size

- One side of the upper back is higher than the other when the child bends over, knees together, with the arms dangling down

With more advanced scoliosis, fatigue may occur after prolonged sitting or standing. Scoliosis caused by muscle spasms or growths on the spine can sometimes cause pain. Nearly always, however, mild scoliosis produces no symptoms, and the condition is usually detected by a pediatrician or during a school screening test.

Diagnosis

The severity of scoliosis and need for treatment is usually determined by two factors:

- The extent of the spinal curvature (scoliosis is diagnosed when the curve measures 11 degrees or more)

- The angle of the trunk rotation (ATR)

Both are measured in degrees. These two factors are usually related. For example, a person with a spinal curve of 20 degrees will usually have a trunk rotation (ATR) of 5 degrees. These two measurements, in fact, used to be the cutoff for recommending treatment. However, the great majority of 20-degree curves do not get worse. Patients do not usually need medical attention until the curve reaches 30 degrees, and the ATR is 7 degrees.

Physical Examination

Adam's Forward Bend Test. The screening test used most often in schools and in the offices of pediatricians and primary care doctors is called the Adam's forward bend test.

The child bends forward dangling the arms, with the feet together and knees straight. The curve of structural scoliosis is more apparent when bending over. In a child with scoliosis, the examiner may observe an imbalanced rib cage, with one side being higher than the other, or other deformities.

The forward bend test, however, is not sensitive to abnormalities in the lower back, a very common site for scoliosis. Because the test misses about 15% of scoliosis cases, many experts do not recommend it as the sole method for screening for scoliosis.

Other Physical Tests.

- The patient walks on the toes, then the heels, and then jumps up and down on one foot. Such activities indicate leg strength and balance.

- The doctor will check leg length and look for tight tendons in the back of the leg, which may cause an uneven leg length or other back problems.

- The doctor will also check for neurological impairment by testing reflexes, nerve sensation, and muscle function.

Identifying the Curvature

Proper diagnosis is important. A misjudgment can lead to unnecessary x-rays and stressful treatments in children not actually at risk for progression. Unfortunately, although measurements of curves and rotation are useful, no test exists yet to determine whether a curve will progress.

Inclinometer (Scoliometer). An inclinometer, also known as a scoliometer, measures distortions of the torso. The procedure is as follows:

- The patient bends over, arms dangling and palms pressed together, until a curve can be observed in the upper back (thoracic area).

- The scoliometer is placed on the back and measures the apex (the highest point) of the upper back curve.

- The patient continues bending until the curve can be seen in the lower back (lumbar area). The apex of this curve is also measured.

- Measurements are repeated twice, with the patient returning to a standing position between repetitions.

- If results show a deformity, the patient will probably need x-rays to determine the extent of the problem.

Some experts believe the scoliometer would make a useful device for widespread screening. Scoliometers, however, indicate rib cage distortions in more than half of children who turn out to have very minor or no sideways curves. They are therefore not accurate enough to guide treatment.

Imaging Tests

Currently, x-rays are the most cost-effective method for diagnosing scoliosis. Experts hope that accurate, noninvasive diagnostic techniques will eventually be developed to replace some of the x-rays used to monitor the progression of scoliosis. To date, imaging techniques under investigation appear to be fairly accurate for detecting scoliosis in the upper back (the thoracic region), but not scoliosis in the lower back (the lumbar region).

X-Rays. If screening indicates scoliosis, the child may be sent to a specialist who takes an initial x-ray and monitors the child every few months using repeated x-rays. X-rays are essential for an accurate diagnosis of scoliosis:

- They reveal the degree and severity of scoliosis.

- They show other spinal abnormalities, including kyphosis (hunchback) and hyperlordosis (swayback).

- X-rays help the doctor determine whether skeletal growth has reached maturity.

- X-rays taken when patients are bending forward can also help differentiate between structural and nonstructural scoliosis. Structural curves persist when a person bends over, and nonstructural curves tend to disappear. (Muscle spasms or spinal growths may sometimes cause nonstructural scoliosis that shows a curve on bending.)

- Children and young adolescents who have mild curves, and older adolescents, who have more severe curvatures but whose growth has stopped or slowed, need x-rays every few months to detect increasing severity. Young people who are diagnosed with scoliosis should keep their x-rays indefinitely in case they develop back problems later in adulthood and need to be re-examined.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an advanced imaging procedure that does not use radiation, as x-rays do. It is expensive, however, and not generally used for an initial diagnosis. MRI can, nevertheless, identify spinal cord and brain stem abnormalities, which some studies indicate may be more prevalent than previously believed in children with idiopathic scoliosis. It also may be particularly useful before surgery for detecting defects that could lead to potential complications.

Protective Measures for Frequent X-Rays

Because young children with scoliosis may need frequent x-rays, parents should be sure that x-ray technicians take all necessary protective measures. Experts are concerned about the long-term effects of radiation on sensitive young organs, particularly about a possible increase in the risk for cancer. Studies have reported an increased risk for cancer in women and men who, because of scoliosis, had been exposed to diagnostic x-rays in their childhood and adolescence.

X-ray techniques have become safer in recent years, and technicians can reduce the hazards with the following simple measures:

- Directing x-ray beams through the patient from back to front, rather than the reverse

- Using x-ray filters that absorb some of the beam

- Using fast film to reduce exposure by 2 - 6 times

- Placing lead aprons or shields over parts of the body that are not being x-rayed

Determining the Extent of the Curve

There are various methods for determining and classifying the extent of the curve.

Cobb Method. The technique known as the Cobb method is used to calculate the degree of the curve.

- On an x-ray of the spine, the examiner draws two lines: One line extends out and up from the edge of the top vertebrae of the curve. The second line extends out and down from the bottom vertebrae.

- The technician then draws a perpendicular line between the two lines.

- Measuring the intersecting angle determines the degree of curvature.

The Cobb method is limited because it cannot fully determine the flexibility or the three-dimensional aspect of the spine. It is not as effective, then, in defining spinal rotation or kyphosis. It also tends to over-estimate the curve. Additional diagnostic tools are needed to make a more accurate diagnosis.

Classifying the Curve. Classification of the curve allows the doctor to identify patterns that can help determine treatments, particularly specific surgical techniques. The following are examples:

- King Classification. The King classification classifies scoliosis curves as one of five patterns, which can help determine surgical treatments. It has limitations, however, and is not very useful for advanced surgical techniques.

- Lenke Classification. Lenke classification takes more features of the curve into consideration and is proving to be more reliable. It includes six curve patterns plus additional factors that modify each of these curves.

Three-Dimensional Modeling Techniques. Advanced computer modeling techniques are able to create three dimensional images using x-rays or other two-dimensional images. They allow doctors to observe the spinal distortions. Eventually, they could reduce the number of x-rays needed to monitor scoliosis and help surgeons determine the best surgical procedures.

Determining the End of Growth

Even if the curve is accurately calculated, it still remains difficult to predict whether the scoliosis will progress. Computer models are being used to better predict risk. One approach requires measuring 21 radiographic and clinical indicators and entering them into a computer program. The technique takes less than 20 minutes per patient, and studies found it to be up to 80% accurate in determining progression of curvature.

One way of predicting whether or not the curvature will progress is knowing when the child will stop growing:

- If the child has years to grow, the curve has more time to progress.

- If the child will stop growing within a year, progression should be very slight. (However, some progression continues in nearly 70% of curves even after the spine has matured.)

Knowing the child's age is, of course, the first step in estimating the end of growth. In addition, other methods can help predict the end of the growth stage. One method is called the Risser sign. It grades the amount of bone in the area at the top of the hipbone. A low grade indicates that the skeleton still has considerable growth; a high grade means that the child has nearly stopped growing and the curve is unlikely to progress much further. The Risser sign, however, differs between genders. In boys, a high grade does not always signify the end of growth.

To Screen or Not to Screen for Scoliosis

Screening programs for scoliosis, which began in the 1940s, are now mandatory in middle or high schools in many states, but there is considerable debate over whether screening should be routine. A recent review of previous studies found that using the forward bend test alone in school screenings is not sufficient, but not enough data exists on the usefulness of other tests in screening programs.

Arguments Against Routine Screening. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend routine screening to detect adolescent scoliosis for the following reasons:

- Screening tests are not accurate and depend too much on the skill of the examiner.

- Schools often refer children with minor curves who are not at any risk for a progressive or serious condition to doctors. Such over-referrals add considerably to the costs of the health system.

- Patients with scoliosis have no greater danger for significant lung problems than the general population until their curves reach 60 - 100 degrees, making early screening unnecessary.

- Such programs result in early treatments that either will not prevent curve progression and surgery or are unnecessary in the first place since curvatures often do not progress at all.

Arguments for Routine Screening. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons recommends that girls be screened twice, at ages 10 and 12, and that boys be screened once, at ages 13 or 14. The American Academy of Pediatrics endorses this recommendation. In one study, however, more than 40% of high school sophomores with newly diagnosed scoliosis showed no signs of the disorder in earlier screening tests.

Other experts make the following arguments for universal screening:

- Universal screening is useful for producing information on scoliosis that may eventually lead to knowledge of its cause and ways to prevent it.

- Braces have proven to be effective, and early treatment can be important.

- Without screening, the chances are slim that children with scoliosis will be diagnosed at an early stage if parents rely only on examinations by a family doctor or pediatrician. Such doctors often do not even look at backs. If they do, they tend to use only the forward bend test, which is not accurate.

Some experts argue that widespread screening would be cost effective if schools had reasonable guidelines for determining which children should see a doctor for further testing. The following are some suggested guidelines for determining the need for a doctor referral:

- Children should be sent to a doctor only if they have a curve of 30 or more degrees.

- Children with curves between 20 and 30 degrees should be screened every 6 months.

Such guidelines would detect about 95% of all genuinely serious cases while referring only 3% of all screened children for follow-up, thereby cutting costs without jeopardizing children.

Treatment

The treatments for scoliosis are not always straightforward. Some young people do not need treatment at all -- only careful observation. When treatment is necessary, several options, including braces and various surgical procedures, can help.

Decision to Treat or Wait

The general rule of thumb for treating scoliosis is to monitor the condition if the curve is less than 20 degrees. Curves greater than 25 degrees, or those that progress by 10 degrees while being monitored, may require treatment. Whether scoliosis is treated immediately or simply monitored is not an easy decision, however. The percentage of cases that will progress more than 5 degrees can be as low as 5% or as high as 50 - 90%, depending on the severity of the curve or other predisposing factors:

Age. In general, the older the child the less likely it is that the curve will progress. Scoliosis in a child under 10, for example, is more likely to progress than scoliosis in an adolescent. Experts estimate that curves less than 19 degrees will progress 10% in girls ages 13 - 15 years and 4% in children older than 15. Therefore, a young man of 18 who has a curvature of 30 degrees may need no treatment because his growth has probably almost stopped, and his gender puts him at lower risk. A young girl of 10, however, with the same curvature needs immediate treatment.

In some rare, severe cases, however, a curve may worsen even after a child has received treatment and stopped growing because of the weight of the body pressing against the abnormal curve.

Gender. Girls have a higher risk for progression than boys.

Location of the Curvature. Thoracic curves, those in the upper spine, are more likely to progress than thoracolumbar curves or lumbar curves (those of the middle to lower spine).

Severity of the Curvature. The higher the degree of curvature the more likely the chance of progression and the more likely the lungs will be affected. Some experts argue that the degree of the curve alone may not identify patients with moderate and severe scoliosis who are at greatest risk for complications and therefore need treatment. For example, spinal flexibility and the extent of asymmetry between the ribs and the vertebrae may be more important than the curve degree in predicting severity in this group.

Presence of Other Health Conditions. Children in poor health may suffer more from stressful scoliosis treatments than other children. On the other hand, children who have existing conditions and are predisposed to lung and heart problems may warrant immediate, aggressive treatment.

Choosing Braces or Surgery

In general, the following criteria are used to determine whether a patient should receive braces and conservative treatments or surgery:

- Braces tend to be used in children with curvatures between 25 - 40 degrees who still will be growing significantly.

- Surgery is suggested for patients with curvatures over 50 degrees in untreated patients, or when braces have failed. In adults, scoliosis rarely progresses beyond 40 degrees, but surgery may be required if the patient is in a great deal of pain or if the scoliosis causes neurological problems.

The choice may not be so straightforward in certain cases, and patients should discuss all options with their doctor.

Predicting the Extent of Curvature Progression

In Children and Adolescents. After a mild curve is detected, a more difficult step is required: predicting whether the curve will progress into a more serious condition. Although as many as 3 in every 100 teenagers have a condition serious enough to need at least observation, progression is highly variable and individual.

Doctors cannot rely on any definitive risk factors for curve progression to predict with any certainty which patients will need aggressive treatment. Some evidence suggests the following factors may help determine patients at lower or higher risk:

- Having a greater angle of curvature. For example, at 20 degrees, only about 20% of curves progress. Young people diagnosed with a 30-degree curve, however, have a risk for progression of 60%. With a curve of 50 degrees, the risk is 90%.

- Curvatures caused by congenital scoliosis (spinal problems present at birth). These may progress rapidly.

- Treatment with growth hormone. (Studies are mixed on whether this treatment poses any significant risk, although strict monitoring is still essential in young patients being given growth hormone.)

Curvatures may be less likely to progress in girls whose scoliosis was low in the back and whose spine was out of balance by more than an inch. Height also comes into play. For example, a shorter-than-average girl of 14 with low-back scoliosis of 25 - 35 degrees, but whose spine is imbalanced by over an inch, would have almost no risk. The same degree of curvature in the chest region of a tall 10-year old girl whose spine was in balance, however, would almost certainly progress.

In Adults. In rare cases, unrecognized or untreated scoliosis in youth may progress into adulthood, with the following curvatures posing low-to-high risk:

- Curvatures under 30 degrees almost never progress.

- Predicting progression at curves around 40 degrees is not clear.

- Curvatures over 50 degrees are at great risk for progression.

Braces and Other Noninvasive Treatments

Braces are generally prescribed to prevent further progression of curves that are at least 25 degrees, and no more than 40 degrees. Patients should have documented progression of the curve, and the child should still be growing.

Results vary widely, depending on the length of time the brace is worn, the type of brace, and the severity of the curve. Determining how effective braces are has been difficult for researchers. Most studies evaluate whether the curve has progressed. There is much less information about whether brace usage actually reduces the number of patients who eventually have surgery.

The great majority of subjects in scoliosis studies are girls. Limited data suggest that in boys compliance rates are low, and braces are not effective. However, compliance with wearing a brace correlates strongly with success rate.

In overweight patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, braces appear to be less effective than in those who are not overweight.

Many experts have questioned whether a brace is any better than nature in halting curvature progress. Early studies found that braces were successful in halting progression in only half of cases (the same rate as no treatment at all). In recent years, however, braces have improved. Many now fit under the arms and can be worn under clothing, so that patients are much more likely to use them for longer periods during the day, which greatly affects their success rates.

Team Approach

Wearing the brace for the prescribed time is difficult but essential for any success. A team approach, with several health professionals involved, is beneficial and often necessary to support the patient through the bracing process. An orthopedic surgeon interprets the x-rays, assesses the potential progression of the scoliosis, and plans the treatment with the patient and family. If a brace is used, an orthotist measures and fits the patient with the device. A physical therapist tailors an exercise program best suited for the patient. A nurse may also coordinate the treatment plans and provide physical and emotional support.

Types of Braces

Full Torso Brace. A full torso brace called the Milwaukee brace was the standard treatment until a decade ago. It is still used particularly for high curves.

The device contains a wide flat bar in front and two smaller ones in back. These bars attach to a ring around the neck that has rests for the chin and back of the head. The best curve correction may occur if the patient lies on their chest when wearing the brace. Some researchers suggest that increasing the tension on the chest straps might add benefit. The brace is also periodically adjusted for growth.

The brace needs to be worn 23 hours a day, with relief during bathing and exercise only. Compliance is a major problem. In one study, only 15% of patients wore the Milwaukee brace as directed. It is a particularly difficult brace to endure wearing, especially during adolescence, where it may lead to social problems with one's peers.

Thoracolumbar-Sacral Orthoses (TLSO). Molded braces called thoracolumbar-sacral orthoses (TLSOs), most often the Boston brace, come up to beneath the underarms and can be fitted close to the skin so they do not show beneath clothing. It appears to be effective for mid-back and lower curves. The risk for curve progression is significantly higher the less time the patient wears the brace. These braces have several problems: they are hot, reduce lung capacity by nearly 20%, and cause mild, temporary changes in kidney function.

Nighttime Braces. Patients wear the Charleston Bending brace and the Rosenberg brace only at night. Some doctors question their value, although they appear to be suitable for small, flexible curves. Still, more than 10% of the patients using either the Boston brace or nighttime braces eventually needed surgery.

Newer braces are being developed in an attempt to improve compliance and results. Some examples are:

- The Providence brace is a computer-fitted device the patient wears only at night. It is specifically designed for the individual curvature abnormalities, and early studies are showing promise.

- A bracing method called the SpineCor uses adjustable bands and a cotton vest that allows flexibility. A recent study comparing SpineCor to no treatment in early scoliosis found the brace achieved correction in a significantly higher percentage of patients compared to controls, and the results were maintained over time.

- The custom-fitted TriaC brace exerts pressure in specific areas of the back to allow greater comfort and flexibility. It may be less conspicuous than some of the older braces.

Studies are needed to determine if these or other new braces provide any additional value over existing ones.

Braces and Quality of Life

Compliance in wearing the braces varies widely. Patients are more likely to wear them at night but often wear them sporadically during the day. Quality of life can vary depending on the type of brace the patient wears. In one study, patients who had the Milwaukee brace reported greater impairment than patients with the Boston, other TSLO, or Charleston braces. The choice of brace should be one that will be the most effective for a particular patient with the lowest impact on the patient's quality of life. Young people often refuse to wear braces, even the newer models. Emotional support from family and professionals is extremely important to help a child accept the process and stay compliant.

Exercise and Physical Therapy While Wearing Braces

For children who need braces, an exercise program helps boost well-being, improves compliance with treatment, and keeps muscles in tone so that the transition period after brace removal is easier.

An exercise and physical therapy program is important to maintain or achieve the following:

- Chest mobility.

- Proper breathing. Aerobic exercises may improve or prevent a decline in lung function.

- Muscle strength (especially in the abdominal muscles).

- Flexibility in the spine. Patients who do exercises improving flexibility in the torso may have improved curvature and less spinal twisting.

- Correct posture. Practicing correct posture, especially in front of a mirror, is an extremely important part of any physical therapy program. A patient who is accustomed to a curved spine may have the sensation of being crooked when first taught to properly align the spine. Practicing in front of a mirror provides a reality check.

- Patients must also learn to conduct daily activities while wearing the brace. Patients tend to comply with physical therapy in the period when the brace is first being used. They typically stop exercising when they have gotten used to the brace, however, and resume exercising only near the time the brace is being removed. Patients who don't stay with the program throughout the duration of brace use have a weakening in the back at the time of removal.

Casting

Serial casting is something that may be used in children with infantile scoliosis only. Candidates are generally those whose scoliosis is progressing. Depending on how quickly the child is growing, casts are changed around every 2 months for children younger than 2, around every 3 months for those aged 3 years, and every 4 months for children 4 years and older.

Improving Lung Function

Airway Ventilation at Night. Some research has focused on the use of airway systems, such as nasal continuous positive airflow pressure, for patients with severe scoliosis and reduced lung capacity. Patients use such systems during the night to force air into the upper airways and lungs. Such systems also can treat sleep apnea, a common sleep disorder.

Breathing Exercises. Breathing exercises may help improve lung function in children with scoliosis and signs of lung problems.

Heel Lifts for Secondary Scoliosis

When a difference in leg lengths causes secondary scoliosis, the health care provider may add shoe wedges or lifts to the patient's heels. It is not clear whether these devices reduce spine curvature.

Surgery

The goals of scoliosis surgery are threefold:

- Straighten the spine as much as possible in a safe manner

- Balance the torso and pelvic areas

- Maintain the correction long term

It takes a two-part process to accomplish these goals:

- Fusing (joining together) the vertebrae along the curve

- Supporting these fused bones with instrumentation (steel rods, hooks, and other devices) attached to the spine

Many surgical variations use different instruments, procedures, and surgical approaches to treat scoliosis. All of the operations require meticulous skill. In most cases, success depends less on the type of operation than on the skill and experience of the surgeon.

The cause of scoliosis often determines the type of procedure. Other determinants include the location of the curve (thoracic, thoracolumbar, or lumbar); single, double, or triple curves, and any rotation that may be present; and how large the curve is.

Parents of patients or adult patients should not be shy. They should always ask the surgeon and hospital about their experience with the specific procedures being considered.

Surgical Candidates

Idiopathic Scoliosis. Surgery is usually recommended for the following children and adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis:

- All young people whose skeletons have matured, and who have a curve greater than 45 degrees.

- Growing children whose curve has gone beyond 40 degrees. (There is still some debate, however, about whether all children with curves of 40 degrees should have surgery.)

Neuromuscular Scoliosis (such as meningomyelocoele and cerebral palsy).Surgery is done when curving has progressed to 40 degrees or more in patients younger than 15 years old. However, this patient group is considered to be at increased surgical risk, particularly those patients with feeding problems, malnourishment, or respiratory difficulties due to the scoliosis. They also have an increased risk of bleeding complications.

Congenital Scoliosis. These children are at a higher risk of neurological injury when having surgery. However, chances for success are higher when surgery is performed at a younger age.

Adult Scoliosis. Due to the increased chance of complications, health care providers are more reluctant to do surgery on this patient group.

Procedures will differ depending on whether a child has idiopathic scoliosis, or scoliosis due to muscle and nerve disorders (such as muscular dystrophy or cerebral palsy). In the latter cases, children also need a team approach to reduce their risks for serious complications.

Preoperative Care

Before the operation, a doctor conducts a complete physical examination to determine leg lengths, muscle strength, lung function, and any postural abnormalities. The patient receives training in deep breathing and effective coughing to avoid lung congestion after the operation. The patient should also receive training in turning over in bed in a single movement (called log-rolling), before the operation. Psychological intervention, using cognitive-behavioral methods that help young patients cope, may be very helpful in reducing anxiety and pain after surgery.

Patients are encouraged to donate their own blood before the operation, for use in possible transfusions. The patient should have no sunburn, rashes, or sores on the back before the operation. These conditions could increase the risk for infection.

Fusion

Most scoliosis operations involve fusing the vertebrae. The instruments and devices used to support the fusion vary, however.

In the fusion procedure, the surgeon will:

- Raise flaps to expose the backs of the vertebrae that lie along the curve.

- Remove the bony outgrowths along the vertebrae that allow the spine to twist and bend.

- Lay matchstick-sized bone grafts vertically across the exposed surface of each vertebra, being careful that they touch adjoining vertebrae.

- Fold the flaps back to their original position, covering the bone grafts.

- These grafts will regenerate, grow into the bone, and fuse the vertebrae together.

Graft Materials. A surgeon takes bone grafts from the patient's hip, ribs, spine, or other bones (these grafts are called autografts). This is the best quality bone. However, because autografts are taken directly from the scoliosis patient, the operation is longer, and the patient has more pain afterward. Researchers are investigating allografts, bone grafts taken from another living person or a cadaver. This would reduce the pain and duration of the operation. Allografts, however, pose an increased risk for infection from the donor.

Newer graft materials that are being used include a biologically-manufactured human bone protein instead of bone grafts. RhBMP-2 (INFUSE Bone Graft) contains a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) that helps the body grow its own bone.

Healing. The healed fusions harden in a straightened position to prevent further curvature, leaving the rest of the spine flexible. It takes about 3 months for the vertebrae to fuse substantially, although 1 - 2 years are required before fusion is complete. Fusion stops growth in the spine, but most growth occurs in the long bones of the body (such as in the legs), anyway. Patients will most likely gain height from both growth in the legs and from the straighter spine.

Patients may walk at a slightly slower pace after fusion, but balance may improve, and sports activities are not restricted after the procedure.

Instrumentation

Harrington Procedure. Until 10 years ago, the standard instruments used in fusion procedures were those of the Harrington procedure, first developed in the 1960s:

- To support the fusion of the vertebrae, the surgeon uses a steel rod, extending from the bottom to the top of the curve. (The surgeon may use more than one rod, depending on the type of curve and whether the patient has outward curvature of the spine.)

- The surgeon attaches the rod by hooks that are suspended from pegs inserted into the bone.

- Similar to changing a tire, the surgeon jacks up the steel rod and then locks into place to support the spine securely. The surgeon is then ready to fuse the vertebrae together.

- After this operation, patients must wear a full body cast and lie in bed for 3 - 6 months until fusion is complete enough to stabilize the spine.

- After 1 - 2 years, the steel rod is not really necessary, but it is almost always left in place unless infection or other complications occur.

The Harrington procedure is very difficult to undergo, particularly for young people, and although the operation can achieve a 50% correction of the curve, studies have reported a 10 - 25% loss in this correction over time. The procedure does not correct the rotation of the spine and, therefore, does not improve an existing rib hump that was caused by the rotation. The operation does not interfere with normal pregnancies and deliveries later in life.

Certain complications may occur from this procedure:

- About 40% of Harrington patients have a condition called the flat back syndrome because the procedure eliminates normal lordosis (the inward curving of the lower back). Flat back syndrome from the Harrington procedure does not cause any immediate pain. In later years, however, the disks may collapse below the fusion, making it difficult to stand erect. This condition can cause significant pain and emotional distress.

- Studies have reported that 5 - 7 years after their surgery, between a fifth and a third of patients who had the Harrington procedure had low back pain. In such cases, however, the pain was not severe enough to interfere with normal activities and did not require additional surgery.

- Children younger than age 11 whose skeleton is immature and who have the Harrington procedure have a fairly high risk for a specific curve progression called the crankshaft phenomenon. This condition occurs when the front of the fused spine continues to grow after the procedure. The spine cannot grow longer, so it twists and develops a curvature. However, in one study that followed patients for 5 - 16 years, crankshaft curve progression was moderate, with the Cobb angle averaging 9 degrees and rotation averaging 7 degrees.

Cotrel-Dubousset Procedure. The Cotrel-Dubousset procedure corrects not only the curve but also possibly rotation. It does not cause flat back syndrome.

With this procedure, a surgeon cross links parallel rods for better stability in holding the fused vertebrae. Patients often go home in 5 days and may be back in school in 3 weeks.

The Texas Scottish-Rite Hospital (TSRH) Instrumentation. The Texas Scottish-Rite Hospital (TSRH) instrumentation is similar to the Cotrel-Dubousset procedure in that it uses parallel rods and other devices that reverse rotation as well as improve curvature. TSRH, however, uses smooth rods and hooks that are designed to make removal or adjustment easier later on if complications arise. Complications are similar to the Cotrel-Dubousset procedure.

Additional Forms of Instrumentation. Other instrumentation procedures have refined the hardware used in the Harrington and Cotrel-Dubousset operations. Some are listed below:

- Luque instrumentation is used primarily in people whose scoliosis is due to problems of nerves and muscles, such as in children with cerebral palsy. After surgeons developed Luque instrumentation to help maintain normal lordosis, experts hoped that bracing would not be needed. Several studies showed, however, that without braces correction was lost after this operation. The procedure may also have a higher risk for spinal cord injury than other standard procedures.

- Wisconsin segmental spine instrumentation (WSSI) is as safe as the Harrington rod and nearly as strong as the Luque instrumentation.

Instrumentation for Anterior Approach. The anterior approach, in which the surgeon does the operation by opening the chest wall, requires specific hardware. Halm-Zielke instrumentation, for example, uses TSRH instrumentation with bone grafts constructed from ribs to prop open the spaces between the disks. It allows true three-dimensional curve correction. However, it does not solve specific problems -- higher risks for kyphosis (an outward curve) and pseudoarthrosis (a false joint at the fusion site). Variants using two rod systems, fusion cages, or other instruments appear to improve this procedure.

Approaching the Spine

Posterior Approach (Through the Back). Many surgeons use a posterior approach for scoliosis, which reaches the surgical area by opening the back of the patient. It has been the gold standard for decades and is generally used with Harrington instrumentation. The posterior approach has advantages and disadvantages:

- Advantages. Surgeons are familiar with it, so fusion rates are excellent, curve correction is good, and it has few complications.

- Disadvantages. Preadolescent children are at risk for the crankshaft phenomenon (a worsening of the curve) later on. (Newer posterior instrumentation, such as the Isola instrumentation, may prevent this occurrence.) The posterior approach also does not always correct hypokyphosis (the loss of normal outward curvature) in the thoracic (upper) spine. The procedure is not always effective for curves in the thoracolumbar region (where the upper and lower spine meet) and may cause spinal abnormalities there.

Anterior Approach (Through the Front). Increasingly, surgeons are using the anterior approach, in which the surgeon performs the operation through the chest wall (called a thoracotomy). With the anterior approach, the surgeon makes an incision in the chest, deflates the lung, and removes a rib in order to reach the spine. This rib can be used during the operation as a strut to support the spine. It also may be repositioned within the patient until it is used for bone grafting during fusion.

The anterior approach also has its advantages and disadvantages:

- Advantages. Because the frontal approach allows the procedure to be performed higher up in the spine than with standard procedures, the patient may have a lower risk for lower-back injury later on. In addition, transfusion rates are much lower with the anterior approach. With increasing experience, the anterior approach is as effective as the posterior approach.

- Disadvantages. It is a newer procedure than the posterior approach. Among inexperienced surgeons, it has a higher risk for complications than the more standard posterior approach. Poorer lung function after surgery has been noted, possibly because the wide chest incision impairs the chest muscles, which can affect lung function afterward. Hardware failure rates may also be higher in the anterior approach than in the posterior approach. Increasing experience with this approach and newer hardware designs are reducing many of these problems.

The Combined Anterior-Posterior Approach. The combination approach uses an anterior approach first, which allows better correction of the problems. The fusion part of the operation is done with the posterior approach. This is a very long and complex procedure. It appears to be safe, however, and is proving to be useful, even in very young patients, for preventing the crankshaft phenomenon. It also may correct large rigid curves and specific severe curves in the thoracic spine.

Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS). The anterior thoracoscopic surgery uses a video-assisted anterior approach and recently-developed spinal instrumentation. Some studies have found no significant differences between the anterior thoracoscopic and the traditional posterior approach in terms of kyphosis, coronal balance, or tilt angle.

This procedure is complicated, and few surgeons are trained to perform it. The surgery is generally used only for single curves in the upper back, or for patients with a curve in the upper back and a compensating curve in the lower back. Some surgeons are now able to operate on areas below the diaphragm, including the lumbar spine. The patients must still wear a brace for 3 months after surgery. Long-term studies to compare results of VATS to those of standard procedures are needed.

Advantages of the anterior thoracoscopic approach include fusion of fewer vertebrae, less blood loss, quicker recovery time (the patient is often out of bed in 2 days), better cosmetic results, and lower transfusion rate. However, the operative time is nearly twice as long as that of the posterior approach.

These new treatments have shown some early positive results, but more research will be needed to determine their true value.

Complications of All Procedures

Complication rates are high with any of the procedures, including the standard Harrington method and the newer Cotrel-Dubousset procedure. A survey of fusion procedures done between 1993 and 2002 for idiopathic scoliosis found the complication rates were nearly 15% in children, and 25% in adults.

Complications for all procedures include allergic reactions to anesthesia and other problems.

Bleeding. Standard procedures increase the risk for major blood loss during the procedure. Patients are encouraged to donate blood before the operation for use in possible transfusions. Children sometimes need more than one transfusion following surgery. Researchers are investigating various methods for reducing the need for transfusions, such as the use of preoperative erythropoietin (rhEPO), which increases production of red blood cells in the bone marrow. Newer endoscopic techniques are reducing the need for transfusions.

Infection. Infection is always a risk with any operation. One study reported changes in the immune system for about 3 weeks after surgery, which indicated a greater risk for infection. Researchers recommended being very vigilant for signs of infection, including those in the pancreas and urinary tract. Doctors also recommend antibiotics, given before and after surgery.

Nerve Damage. Patients often worry about neurological injuries, but the risk is actually very low. In general, nerve injury occurs in 1% of patients, with the risk highest in adults. If neurological damage occurs, it most often causes muscle weakness. Paralysis is very rare and can be prevented using monitoring techniques during the operation. Nearly all monitoring procedures use a so-called wake-up test, in which the patient is brought out of anesthesia during or at the end of the procedure and assessed for sensations to be sure no injury has occurred. One simple method is to wake patients up in the middle of their operations and ask them to wiggle their toes. More sophisticated methods measure the electrical activity of the spinal cord. If the monitor indicates a fall in electrical response and possible injury, the surgeon makes adjustments to avoid further damage to the spinal cord.

Pseudoarthrosis. If the fusion fails to heal, pseudoarthrosis, a painful condition in which a false joint develops at the site, may develop. In one study, teenagers who smoked and heavier adolescents (over 154 pounds) who had hyperkyphosis (hunchback) were at higher risk for this complication. The anterior approach may pose a higher risk for pseudoarthrosis. One study reported that pseudoarthrosis may be underdiagnosed, and rates may average 20% after surgery, therefore acting as a major contributor to post-surgery pain.

Disk Degeneration and Low Back Pain. Fusion in the lumbar area produces great stress on the lower back and eventually can cause disk degeneration. Loss of trunk mobility, balance, and muscle strength from surgical treatments can also cause lower back pain and chronic problems in future years. Patients who are surgically treated with fusion techniques lose flexibility. Their back muscles may be weakened if they were injured during surgery. In most cases, however, the consequences are mild to moderate.

Lung Function. Some patients may develop serious lung problems after surgery. These complications are highest in children whose scoliosis is due to neuromuscular problems, such as spina bifida, cerebral palsy, or muscular dystrophy. Lung problems can develop up to 1 week after surgery. Lung function may not become completely normal until 1 - 2 months after surgery.

Other Complications. Other problems can include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Hooks dislodging or a fused vertebra fracturing

- Gallstones

- Pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas). Among adolescents, this complication tends to occur more often in those who are older or who have a lower body mass index.

- Intestinal obstruction

Postoperative Therapy

Patients must do breathing and coughing exercises shortly after the procedure and continue them through the recovery process to rid the lungs of congestion. The patient is usually able to sit up the day after the operation. Most patients can move on their own within a week. A brace may be necessary, depending on the procedure. With the anterior approach in the upper back, patients may have some trouble with activities involving the arms and hands, such as tying shoes and cutting food. However, occupational therapy using stretching and strengthening exercises, may allow for full resumption of daily activities within 3 months, including dressing, bathing, and grooming.

Some pain always follows these procedures, requiring intravenous administration of strong painkillers right after the operation (endoscopic procedures may require only mild pain relievers). NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin, Motrin, and Advil) for pain relief right after fusion may increase the risk for fusion failure. Consult with your doctor before you or your child take any pain medication after surgery.

Patients are often concerned that surgery will stiffen their backs, but most cases of scoliosis affect the upper back, which has only limited movement, so that patients do not notice much difference. It may take a year or more for muscle strength to return. In some cases, the operation cannot completely correct the curve, and one leg may be shorter than the other. Heel lifts may help in this case.

Revision (Salvage) Surgery

Patients may need a corrective procedure called revision or salvage surgery, usually for one of these reasons:

- Failure of the previous procedure

- Curvature progression around the fusion site

- Disk degeneration

- Poor posture alignment

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Growing Rod Technique. This technique is used for very young children in whom bracing has not helped. Instead of doing spinal fusion, doctors surgically insert a rod into the patient's back. The patient will have more surgeries every 6 months to extend the rod so that the spine can continue to grow. Some growing rod techniques use a single rod, while others use two rods. Studies suggest that dual rods are stronger than single rods, which may help provide better spinal stability and correction.

Vertebral Body Stapling and Anterior Spinal Tethering. Surgeons do these procedures using an anterior approach surgery and without fusion. Vertebral body stapling is an experimental technique that may prevent curve progression in some young patients with curves less than 50 degrees. It involves stapling the outer curve of the side of the spine facing the chest, which helps stabilize and reduce progression of the inner curve. The procedure uses a special metal device that is clamp-shaped at body temperature. The device can be straightened when subjected to cold temperatures and inserted into the spine. When warmed up, the staple returns to its clamp shape and supports the spine. While short-term results have been favorable, long-term results are not yet available.

Considerations for Adults with Previous Scoliosis

Adults who were treated with surgery for scoliosis in their youth are at risk for disk degeneration and spinal fusion failure.

In most adults with previous scoliosis, moderate exercise is not harmful and is extremely important for maintaining healthy, supportive muscles, and preventing disk degeneration. However, people who have only one or two mobile lumbar vertebrae below the area that was fused during surgery should avoid activity or exercise that causes excessive twisting on the spine. Some experts believe this may accelerate spinal degeneration.

Treatment for Adult Scoliosis

Nonsurgical Treatment of Adult Scoliosis

In most cases of adult scoliosis, nonsurgical care is preferred, if possible. This can include patient education, exercises, and medical treatments. Braces are not useful.

One center reported that epidural steroid injections were a beneficial alternative to surgery in patients with degenerative lumbar scoliosis.

Surgical Treatment in Adult Scoliosis

Candidates for Surgery. In general, pain is the most common reason for surgery in adult scoliosis. Surgery may be recommended in the following cases:

- Curvatures over 50 degrees with persistent pain

- Curvatures over 60 degrees (surgery is almost always recommended in this case)

- Progressive mid and low back curve or low back curve with persistent pain

- Reduced heart and lung function. Most surgeons, however, will not operate on adults with severely impaired lung function and heart failure. Once this has occurred, surgery will not help improve lung capacity, and it may cause the condition to get worse, at least temporarily.

- Significant deformity is present. Adults should not expect to achieve a completely straight spine, however. There is a high risk for nerve damage if the spine is over-corrected, and an adult spine is less flexible than a child's. Nevertheless, the correction usually achieves an acceptable cosmetic improvement.

Surgeons prefer to operate on adults under 50 years old, although surgery may be appropriate in some older people.

Standard Scoliosis Procedures in Adult Scoliosis. The procedures involve the following, depending on whether the patient had been previously treated or not:

- In patients who have not had previous treatment, and who have degenerative lumbar scoliosis, the procedure is often a diskectomy (removal of the diseased disks), followed by scoliosis procedures (instrumentation and fusion).

- In patients with previously treated scoliosis, the only remedy is removal of the old instrumentation, extension of the fusion, and implementation of new instrumentation and bone grafts.

Surgical procedures in adult scoliosis are complex. They are done only after careful consideration, and all nonsurgical methods, have been exhausted. Adults have a much higher risk than children for complications, including pneumonia, infection, poor wound healing, and persistent pain. In addition, procedures in adults often involve fusion in lumbar and sacral areas (the low back), which can cause several complications. Some experts believe that the risks of operations in this area nearly always outweigh any benefits in adults. Most studies on adults have also reported low success rates.

Others argue that without an operation, the back will become unstable and painful. In addition, most studies on adults report on procedures using the old Harrington instrumentation techniques. Advances in instrumentation are increasing success rates in adults. In a recent study, for example, adults who underwent anterior fusion and instrumentation had excellent results. In another study of newer generation instrumentation, 87% of adult patients reported satisfaction.

Wedge Osteotomy. Researchers are investigating wedge osteotomy in patients with mature spines, as corrective surgery and as an alternative to braces. In this procedure, a surgeon cuts wedges of bone from the concave side of the curve. The surgeon then straightens the spine by inserting a temporary rod and closing the cut sections. The patient needs to wear a brace and restrict activity for about 12 weeks or until the bone has healed. The patient can resume normal activities when a surgeon removes the rod, and the spine is mobile.

Resources

- www.scoliosis.org -- National Scoliosis Foundation

- www.srs.org -- Scoliosis Research Society

- www.scoliosis-assoc.org - - Scoliosis Association

- www.aaos.org -- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

- www.niams.nih.gov -- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

References

Aebi M. The adult scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(10):925-948.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Statement of Endorsement: Screening for Idiopathic Scoliosis in Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5): 1069

Budweiser S, Moertl M, Jörres RA, et al. Respiratory muscle training in restrictive thoracic disease: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(12):1559-65.

Coillard C, Circo A, Rivard C. A prospective randomized study of the natural history of idiopathic scoliosis versus treatment with the SpineCor brace. Scoliosis. 2012;7 Suppl 1:O24. [Epub ahead of print]

D'Astous JL, Sanders JO. Casting and traction treatment methods for scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38(4):477-484.

Everett CR, Patel RK. A systematic literature review of nonsurgical treatment in adult scoliosis. Spine. 2007;32(19 Suppl):S130-134.

Ferri FF. Ferri's Clinical Advisor. 2011, 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA. Elsevier Mosby: 2011.Pp. 990.

Fong DY, Lee CF, Cheung KM, Cheng JC, Ng BK, Lam TP, et al. A meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness of school scoliosis screening. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(10):1061-71.

Freeman III, BL. Scoliosis and Kyphosis. In: Canale ST, Beatty JH. (eds.) Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

Guille JT. Fusionless treatment of scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38(4:541-545.

Hedequist DJ. Surgical treatment of congenital scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38(4):497-509.

Johnston CE. Preoperative medical and surgical planning for early onset scoliosis. Spine. 2010;35(25):2239-2244.

Katz DE, Herring JA, Browne RH, Kelly DM, Birch JG. Brace wear control of curve progression in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1343-52.

Lonner, B. S. Emerging minimally invasive technologies for the management of scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38(3): 431-440.

Negrini S, Minozzi S, Bettany-Saltikov J, et al. Braces for idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents. Spine. 2010;35(13):1285-1293.

Patil CG, Santarelli J, Lad SP, et al. Inpatient complications, mortality, and discharge disposition after surgical correction of idiopathic scoliosis: a national perspective. Spine J. 2008 Mar 19 [Epub ahead of print]

Richards BS, Vitale M. Screening for Idiopathic Scoliosis in Adolescents: Information Statement. AAOS-SRS-POSNA-AAP. Available online.

Rose PS, Lenke LG. Classification of Operative Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Treatment Guidelines. Orthop Clin N Am. 2007;38:521-529.

Sarwark J, Sarwahi V. New strategies and decision making in the management of neuromuscular scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38(4): 485-496.

Shaughnessy WJ. Advances in scoliosis brace treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38(4):469-475.

Spiegel DA, Dormans JP. The Spine. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. GemeIII, JW, Behrman RE. (eds.) Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 19th ed. Philadelphia,Pa: Mosby Elsevier;2012.

Sucato DJ. Management of severe spinal deformity: scoliosis and kyphosis. Spine. 2010;35(25):2186-2192.

Trobisch PD, Samdani A, Cahill P, Betz RR. Vertebral body stapling as an alternative in the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2011;23(3):227-231.